by Quendrith Johnson, Los Angeles Correspondent

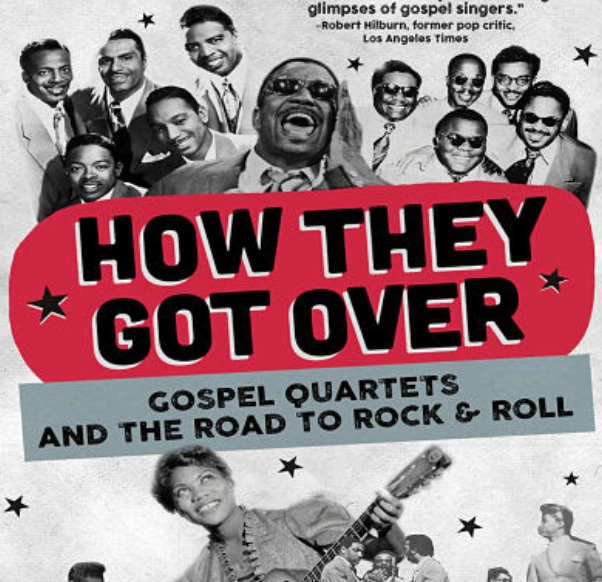

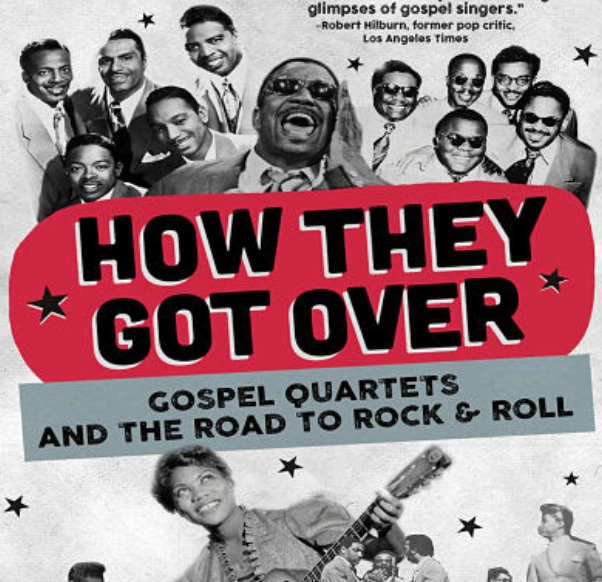

After watching documentary HOW THEY GOT OVER, directed by Robert Clem, more than the music of the Soul Stirrers, Dixie Hummingbirds, Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, Sensational Nightingales, the Davis Sisters, and other featured artists stays with you. There’s Sister Rosetta Tharpe in all her glory, guitar on the lap, kind of changing the world for all to see. Released this month from First Run Features, Clem’s sonic odyssey is a history lesson, a celebration, and a glimpse into the sound that listeners now have baked into their musical memory.

This is the power of the Gospel influence that pushed greats like Sam Cooke once of the Soul Stirrers, Lou Rawls, and Wilson Pickett to “cross over” to the so-called mainstream. They blazed a musical trail not just in America, but around the planet and into the foundation of a movement that became Rock’n’roll as we know it today.

Here’s Alabama naive Robert Clem, who is actually the proverbial ‘son of a Preacher man’, on this astonishing look-back at a moment in time, geopolitics, and at the unexpected birth of a new rocking sound that continues to shape our lives in real time.

First Look from First Run Features – HOW THEY GOT OVER

How They Got Over – Official Trailer from First Run Features on Vimeo.

Q: This documentary is so sweeping in covering Gospel groups, how did you choose?

ROBERT CLEM: I selected what I thought were the best performances from TV Gospel Time, the low-budget, syndicated program from the early 60s produced for a Black audience. Where possible I located and interviewed surviving members of the groups whose performances I wanted to use.

Most were in their 70s and 80 and most have since passed away.

Some groups like the Swan Silvertones and Pilgrim Travelers were left out for lack of any footage we could use but we do have audio tracks from many of the these other legendary groups.

Q: Perhaps the first question for you should have been, what took you on this sonic journey?

ROBERT CLEM: I am from Alabama, my father was a preacher, but I never heard of these quartets, since they played to black audiences and were pretty much invisible to whites. For example, they received no press coverage in the major white-owned newspapers and were never on network television.

Then I saw, and was blown away by, the Blind Boys of Alabama in The Gospel at Colonus, the hit show by Lee Breuer at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the 1980s. Years later I had the idea of making a film about them, but was told a film was already underway (I don’t think it was ever completed).

I have always been a fan of African American music dating from Bo Diddley to Motown to Soul to the Chambers Brothers and so on.

With black gospel quartets I found myself drawn to the sheer passion and high energy in their music. So off I went.

Q: These foursomes, as pointed out, are the forerunner of so much in music, can you condense it?

ROBERT CLEM: If you look at the music that was popular with white audiences up into the 1940s and 50s, it was pretty staid by today’s standards. The Hit Parade on national TV in the mid 50s had songs like “How Much is that Doggy in the Window?”

Perry Como and Lawrence Welk were hugely popular.

Harmony groups like the Andrews Sister pretty much stayed tied to the microphone like the old fashioned white barbershop quartets.

Black quartets through sheer ambition, competitiveness and a desire to put on a show developed new techniques of showmanship designed to fire up their audiences with religious fervor.

Mick Jagger’s moves come directly from gospel quartets; it was all about working up the crowd, to make them laugh, shout and move to the beat.

Their emotion was another big factor; whether it was real or not — and with most of these singers it was because of where they came from — this too became a goal of subsequent popular music, to “move the audience to another place.”

Q: It is heartrending to see how many of these great artists have passed away, how did that effect your putting the final cut together?

ROBERT CLEM: Their passing was expected.

I am just glad I was able to make a connection with them and was able to get them to tell their stories before they died.

They’re still alive to me.

Q: Is it a fair argument to say that Rock’n’roll took the thunder from these groups, or can the two stories exist in parallel without casting a bad light on either?

ROBERT CLEM: Gospel, the Blues, and Rhythm and Blues all became the major influence for Rock’n’roll, and although some people see cultural appropriation in this, to me it simply a tribute to the people who created the original forms.

Their music was transformative and we were the beneficiaries.

White rock-and-rollers have produced some great music, and they knew and often acknowledged what their sources were even if many in their audiences didn’t.

Q: What do you think are the groups people have never heard of that should be remembered by everyone?

ROBERT CLEM: That’s a hard one.

Most people know the Blind Boys of Alabama because of their recent success but few of the others.

I think we should remember them all.

And by the way, the female groups in the film are especially unknown but truly phenomenal.

Q: Is singing something that can address repression or other issues like no other art form, or do you think these visuals in the documentary speak louder, and, also is this how they finally “got over” in your film?

ROBERT CLEM: African slaves adopted Christianity because of its message of salvation, future redemption, hope of eventual freedom. In the Jim Crow 20s, 30s and 40s, Gospel music was spiritually uplifting, its message hopeful, as quartets crisscrossed the South dodging the police and carrying a message to Blacks that was subversive: We shall overcome.

The popularity of Gospel quartets dovetailed with the rise in Black expectations and the evolution of Black civil rights.

‘How They Got Over’ as a title has three different iterations: how these individual singers were able to get over poverty, and find a way to a dignified way of making a living, how blacks as a culture got over their repression by working together, and how singers found ways in their performances to move their audiences and lift their spirits.

I think another outcome of this whole story is how black music ultimately did cross over, and in the process was a major force in bringing whites and blacks into a common culture.

It “opened the door” as Linwood Heath says in the film.

We all know there is a lot of coming together that still needs to happen.

In closing, Clem adds, “besides watching the film, people can find most of these groups still have LPs and digital music online.” Streaming of the documentary, and the DVD Launch day dropped in early May, so HOW THEY GOT OVER is now on Apple TV, iTunes & Vimeo On Demand, and there is also a DVD Bonus Features.

The DVD Bonus items include: Sister Rosetta Tharpe hosts TV Gospel Time and performs Down by the Riverside (5:44). Also The Barrett Sisters of Chicago singing Jesus Loves Me on TV Gospel Time (3:10), and the Blind Boys of Mississippi host TV Gospel Time with a hard gospel rendition of Leaning on the Everlasting Arms (4:21).

Thanks so much to Robert Clem and all the musicians features in HOW THEY GOT OVER, and noting the theme, if you listen to Curtis Mayfield, from his album “Superfly” the lyrics talk about “the game he plays, he plays for keeps… trying to get over. Gambling with the odds of fate trying to get over, trying to get over.” The power of this theme is still very relevant.

Please visit HOW THEY GET OVER, and seek your own path to the sound that changed the world here.

# # #