By Matt Jacobs, Screenmancer Reviewer

First, an introduction about SAVING ATLANTIS. Matt’s review follows, and with some words from David Baker (Justin Smith is on location)…

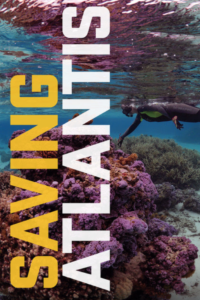

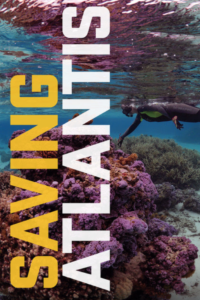

SAVING ATLANTIS is a feature documentary directed by Justin Smith and David Baker and produced by Oregon State University. It focuses on the dramatic loss of coral reef ecosystems around the world, the impact of that decline on the human communities that depend on them and those who are going to uncover the causes and solutions before it’s too late.

The film follows several story threads, including: renowned scientists looking to unlock the microbial secrets to coral survival; a mysterious coral reef in Colombia that has withstood over five hundred years of human pressures but now faces its greatest threat; and a group of young aboriginal students in Australia working to restore the ancient connections of their people to a marine habitat just as it could disappear forever.

The film braids these stories with the science behind corals, speaking with the top researchers who study these animals and taking a global journey that celebrates the majesty and mystery of coral habitats, outlines the daunting challenges communities face and follows those who are making a desperate attempts to preserve them for future generations.

Filmed in Australia, the South Pacific, Hawai’i, the Caribbean and the Red Sea, SAVING ATLANTIS is a worldwide tour of one of the most important issues of our time.

Reviewed by Matt Jacobs, Based in NY

Portland State University is a public researcher University that has produced a very stunning and informative documentary about the erosion of coral reefs and that erosions impact on the environment and our lives.

Saving Atlantis seeks to first explain the ecological importance of coral to the planet, how it’s being damaged due to climate change, and finally what we can do about it. Fairly early on in the film we see a Latin American gentleman teaching a class of children about coral reefs. He asks the question “what is coral”.

It’s a very good question because everyone basically knows what it is, but most people don’t really know what it is. He explains that Coral is both a plant and an animal, and that many oceanic life forms naturally are drawn to it.

Coral becomes a home to both fish and microbs, so it is basically a living thing that contains other living things. Humans are also dependent upon it because it brings fish to the coastline that provides a food source to millions of people, and it protects the shoreline. Hence the term barrier reef. Coral is basically to the ocean what trees are to the land.

It’s a very important subject, and Saving Atlantis pulls out all the stops in describing it in the most beautiful and evocative ways possible.

The audience is treated to slow motion underwater cinematography, long majestic drone shots and time laps photography while listening to the plea’s of both fishermen and environmental scientists.

That combined with Peter Coyote’s urgent narration make it nearly impossible for the viewer to not care for the fate of the kaleidoscopic colored coral.

Exotic locations such as French Polynesia, Columbia, Australia, and Saudi Arabia give the film an additional sense of sensuality and seriousness. I find marine biology particularly interesting, and get easily seduced by beautiful cinematography probably more so than the next guy, but I have to admit I started to tune out a little after the first 45 or 50 minutes.

Some of the information was a little redundant and not entirely necessary. For example I didn’t need to hear about how mucus is extracted from coral. I also found the Philip Glass-like score more than a little manipulative. The film clocks in at an hour and 15 minutes and I couldn’t help feeling that if the film makers had edited it down by about a third they could have changed it from a short feature to a more effective long short film (please excuse the oxymoron).

If you’re going to make a documentary about anything you almost have to find the subject matter fascinating, so it’s a common and understandable mistake of documentary filmmakers to think the audience will find the film’s subject as interesting as they do.

The film focuses on the victims both human and animal of coral erosion and bleaching due to global warming, the heroic grass root activists trying to save the coral, and the scientists who have found some ingenious ways to regrow it. It does not discuss the corruption, corporate greed, and industrial apathy that’s causing a lot of the damage in the first place.

The filmmakers clearly wanted to focus on the positive and keep the film uplifting, which is admirable. Personally I would have liked to see a little more anger, finger pointing and hostility, but that might say more about me than it does the film.

Good work Oregon State University. You’re fighting the good fight!

10 Things You Need to Know About Saving Atlantis from David Baker

What do you think is the most pressing thing people should know about climate change?

DB: If we continue to burn fossil fuels at the rate we are today, most coral reefs will be destroyed, if not within our life time, within the lifetimes of our children. Most scientists we’ve interviewed agree on this.

How many groups out there are actively saving the planet as we speak?

DB: There have to be thousands of groups. From coral health monitoring projects by citizen scientists to volunteers taking youth groups to reefs and then researchers working on bold genetic projects, the range and number is massive. That’s what gives us hope. Stopping climate change is clearly the most critical thing that needs to happen to save corals, but the problems are complex and many, and lots of people who love corals are working on them.

How can we change our carbon footprint in and around our homes?

DB: Everything helps. Bike commuting, taking public transportation, cutting back on flights, eating mostly plants, modernize insulation…it all has an impact. And what’s more important is to advocate for and vote for leaders who have bold, aggressive solutions when it comes to sustainable energy, and who support international collaboration on climate reduction. In Oregon that’s something we can do at home because we vote by mail.

Did the indigenous populations change how you saw the climate crisis?

DB: Absolutely. We learned that indigenous communities lived, for example, along the Great Barrier Reef for tens of thousands of years in harmony. We can learn how to be better stewards of resources from indigenous wisdom. Western scientists call this “traditional ecological knowledge” and they are incorporating it more and more in their research along with the empirical data they gather.

When most feel like giving up on trying to un-tip the scales of change in the weather and our seasons, how do you give them hope?

DB: What gives me hope is even the most pessimistic and cynical scientists we met, those who are convinced that the window is closing and there’s little hope to save reefs…these are some of the people who go to work every day and work the hardest, gathering data, sharing it with political leaders, haranguing them when they don’t listen. People who care about reefs are not quitting. There’s hope in that.

Is Earth Day really morphing into Climate Crisis Day, or are they really the same thing?

DB: We need Earth Day every day. We need to both celebrate the wonder of the natural world and the resources it provides to humans. And we need to take dramatic action to protect what remains. We hope this film can help do both of these things.

Which population in the animal kingdom is most vulnerable, as many scientists usually put frogs at the top of this list?

DB: There are so many that it’s hard to keep track. One recent paper I read shows that between 1970 and 2012, vertebrate species have declined by around 60% overall according to global data sets. Frogs and amphibians are certainly some of the first and worst affected by global change.

Is Western culture equipped to make the perceptual changes necessary to fight off a climate disaster, or is the dominance over the so-called “animal kingdom” just so ingrained?

DB: We do need an ideological shift. That’s where looking to indigenous communities and adopting different ethics when it comes to use of natural resources is important. Now our own very survival as a species depends on conservation of resources, so maybe that’s the change we need. As filmmakers, we always try to include the human cost of losing ecosystems. Self-interest is a powerful motivator.

What did you see that gave you instant perspective on a warming planet?

DB: The bleached reefs of Mo’orea, French Polynesia were shocking to see. The South Pacific is so far from massive population centers and continental sources of pollution. The fact that even way out there, reefs were damaged by climate change-related events is shocking.

If you could give someone three ways to change their daily habits to fight against climate erosion, what would they be?

Vote, vote and vote. If politicians deny, ignore or don’t grasp the scale of the ongoing climate emergency, they should be voted out of office as soon as possible.

SAVING ATLANTIS has been recognized by the following:

Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI)

Official Selection: Newport Beach Film Festival

Official Selection: AmDocs

Official Selection: Bend Film Festival

Official Selection: Guam International Film Festival

Official Selection: Emerald Earth Film Festival

Official Selection: United Nations Association

Environmental Film Festival

Watch it now.

Gravitas Ventures released SAVING ATLANTIS on VOD on Nov. 12, on numerous platforms including: Comcast, Dish Network, Spectrum, Verizon Fios, iTunes, Prime Video, Vudu, Google Play, Vimeo, among others.

Screenmancer Thanks Matt Jacobs, David Baker, Justin Smith & the SAVING ATLANTIS Team.

# # #